Karl Barth on Biblical Exegesis

This article is the first of a series of two articles explaining Karl Barth’s approach to biblical exegesis. In this article I will focus on Karl Barth’s method of spirit-led discernment in interpreting the Bible. Where appropriate, I will contrast Barth’s position with that of Adolf von Harnack, for whom the historical-critical method is supreme in biblical exegesis. In the second article I will explain Karl Barth’s view of the subordinate role of historical-critical methods in biblical exegesis.

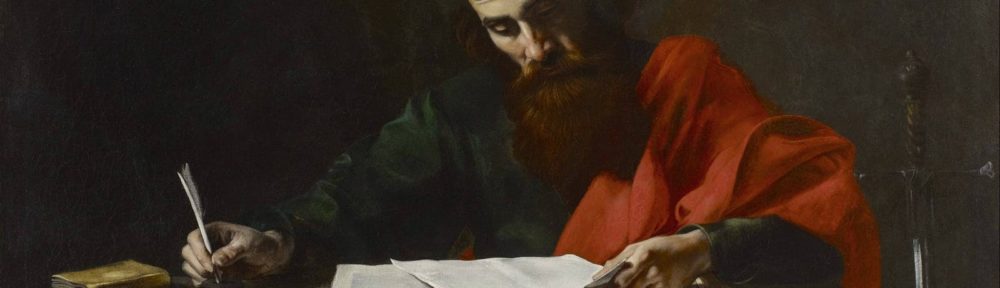

I will limit my exposition of Barth to three sets of writings: 1) Karl Barth, “Foreword to the First, Second, and Third Editions of The Epistle to the Romans,” in James M. Robinson, ed., The Beginnings of Dialectic Theology, vol. 1, pp. 61-61, 88-99, 126-130 (cited as 1F, 2F, and 3F, respectively); 2) Karl Barth, The Epistle to the Romans (pictured to the right), pp. 27-42 (cited as R); and 3) “The Debate on the Critical Historical Method: Correspondence between Adolf von Harnack and Karl Barth,” in James M. Robinson, ed., The Beginnings of Dialectic Theology, vol. 1, pp. 165-187 (cited as B).

Karl Barth: God as “Utterly Distinct from Men”

Karl Barth’s approach to exegesis begins with presuppositions about God and the gospel. For Barth, God exists in radical contrast—even contradiction (R-39)—with creation: he is “utterly distinct from men (R-28).” With Kierkegaard Barth speaks of the “infinite qualitative difference” between God and the world. God is so totally Other that people are inherently “incapable of knowing Him (R-28).”

The gospel, then, is the proclamation of this God who is totally Other, and his salvation that comes to humanity initiated completely by grace. The gospel is “not a religious message to inform mankind of their divinity,” nor instructions in how to be divine (R-28). Rather, it is the jarring self-disclosure—or revelation—of a holy God to humanity, the perception by people of what was previously unperceivable to them (R-28).

Jesus, the bearer of the gospel, is a visible point on the line of intersection between God and world, between unknown and known (R-29). Given the position of God as radically over-against humanity, the gospel reveals him as humanity’s norm. God sits in judgment over humanity (R-168), thereby creating what Karl Barth frequently refers to as a “crisis (2F-95)” for humanity: the proclamation of an absolute and holy God calls contingent, sinful humanity into question.

Karl Barth is careful to point out that scripture itself is also contingent on God. Scripture is not revelation, but rather Jesus Christ is the revelation of God—i.e., God’s action in the form of human flesh. Scripture is simply a witness or pointer to this revelation (B-178, 179). In the same way that Paul as an apostle points beyond himself, deriving his authority solely from God (R-28), so the scripture points beyond itself to the self-disclosure of God in Christ.

Karl Barth: Biblical Exegesis as Spirit-led Discernment

Therefore, for Karl Barth, the purpose of reading scripture is not Harnack’s separation of kernel from husk (R-28). Rather, the purpose is to discern “the Word in the words” of scripture (2F-93). Here Barth understands “the Word” as “the correlation of ‘Scripture’ and ‘Spirit’ (B-177),” or the communication of the Holy Spirit—the “Spirit of Christ (3F-127)”—through the human words of scripture (B-181). Therefore, for Barth the heart of exegesis is a Spiritual process by which the reader strains to understand what the Holy Spirit is speaking through a particular text. It is not a matter of human capacity or experience, but rather God acting upon us (B-181). Barth notes the mysterious circularity of this process whereby the “content” of the scripture—God’s self-revelation in Christ—is also the Spiritual means of understanding that content: “the content itself must be the road, the speaking voice must also be the hearing ear (B-178).” The “content” is not the mere object of study, but is also the Subject that reflexively reveals itself (B-167).

In practice, Karl Barth’s exegesis proceeds by presupposing the “infinite qualitative difference” that characterizes God’s relationship to humanity—i.e., by presupposing “that God is God (2F-95)”—and actively engaging in a process of deep reflection on the scripture, modeled after historic interpreters such as Calvin (2F-92). As Calvin did, the exegete must try to think the thoughts of the text until the historical separation between author and interpreter disappears and the theme of the text, which is the same for all time, is directly confronted (2F 92, 93).

Barth refers to this process as “the old doctrine of inspiration (1F-61).” The exegete must measure all the words of the text relative to its subject matter, ultimately relating them to the Word of God spoken by the text (2F 93). The exegete must be faithful to the author, writing not about him but with him—i.e., not judging him, but understanding him and taking him seriously (3F 127-129). When confusion arises, the exegete must be self-critical, presuming first a lack of understanding in oneself, and not the author (3F 127, 128).

Given the contingent nature of people and the scripture, this process of energetic Spirit-led interpretation cannot lead to completely certain theological results. Karl Barth acknowledges that the presuppositions with which he approaches the interpretive task could be shown to be wrong in the future (2F-95, B-175). He writes, “All human work is only preliminary work, and this is true of a theological book more than of any other (2F-88)!” Accordingly, he calls his readers to a critical and sober evaluation of his work (2F-97). Nevertheless, despite such acknowledged uncertainties, Barth continues to advocate this Spiritual mode of scriptural explanation (2F-94).

In the next article in this series I will explain Karl Barth’s view of the subordinate role of historical-critical methods in biblical exegesis.

I cited this article in my first theology paper in seminary on the doctrine of scripture.

Thanks for helping me understand a little more about Barth. My assigned texts turned out not to be sufficient.

I wonder what my professor will say…

Glad it was helpful. I’m guessing your professor won’t mind as long as what you’ve said is textually grounded (which my article obviously is). Enjoy seminary!

Pingback: Theosis and Our Salvation in Christ | Orthodox-Reformed Bridge

He opposes any attempts to closely relate theology and philosophy, although Barth consistently insists that he is not “anti-philosophical.”

Pingback: Difference Between A Religious Study Major And A Theologian -