Irenaeus: Against Heresies

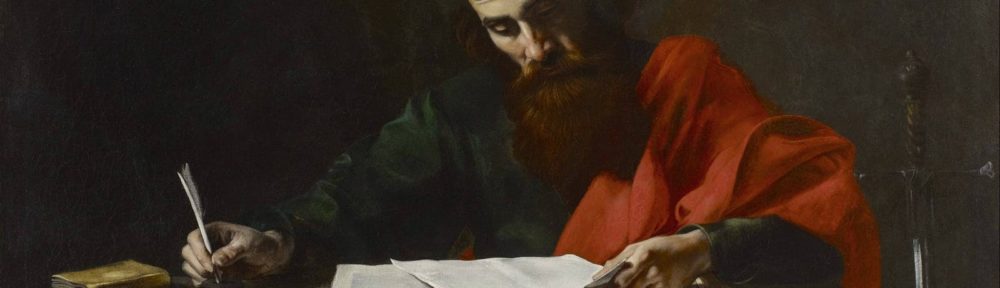

In Against Heresies (in Early Christian Fathers [ECF], pictured to the right) Irenaeus articulates multiple arguments against Gnostic teaching. First, Irenaeus responds to a Gnostic claim that the message preserved in the Gospels is flawed since it was preached before the Apostles came to perfect knowledge (ECF 370). He counters by noting that the apostles came to perfect knowledge of the gospel immediately following the resurrection and baptism in the Holy Spirit (ECF 370). He further argues that the Gospel accounts were written after this perfecting event, and thus accurately portray the true Gospel message (ECF 370). Therefore, the Gnostic claim that the Gospel accounts are not fully authoritative has no basis. Concluding his argument, Irenaeus states that to disagree with the teachings of the apostles as recorded in the Gospels is to despise Jesus Himself and the true gospel message (ECF 370). Therefore, by this claim of imperfect apostolic preaching the Gnostics badly undermine their claim to truth.

In a related argument, Irenaeus attacks the Gnostics in their claim that only selected parts of the apostolic writings are authoritative. According to Irenaeus, the Ebionites accept only the Gospel of Matthew, Marcion only parts of the Gospel of Luke, and Valentinus the Gospel of John (ECF 381-82). Although he does not spell out his particular scriptural arguments at that time, Irenaeus notes that his strategy is to refute the Gnostics from their preferred Gospels (ECF 382). An example of such refutation might be his argument against the Docetic teaching: if Jesus was the Truth—as claimed in the Gospel of John (14.6) and embraced by some Gnostics—why would He deceive by only appearing to be human (ECF 386)? Thus, Irenaeus refutes the Gnostics whether they accept or reject scripture.

Yet another Gnostic claim about scripture is that it cannot be interpreted correctly without their oral tradition (ECF 370). They claim access to the true oral tradition that was secretly passed from the apostles to the Gnostic teachers (ECF 370-71). Irenaeus counters this claim by noting that the catholic church can trace a carefully guarded interpretive tradition from the apostles to the contemporary church leaders (ECF 371). He enumerates the lineage of the exemplary Roman church episcopate, proving the connection of present catholic doctrine with the apostles and Jesus Himself (ECF 372-73). Furthermore, Irenaeus notes that “even if the apostles had known of hidden mysteries, which they taught to the perfect secretly and apart from others, they would have handed them down especially to those to whom they were entrusting the churches themselves (ECF 371-72).” Therefore, since the true apostolic oral tradition was passed from Jesus and the apostles to the contemporary church leaders, the Gnostics have no claim to a different, secret oral tradition whereby they correctly interpret the scriptures. They are cast back onto their own authority alone (ECF 371).

Irenaeus’ summary refutation is that the Gnostics’ inconsistent, “slippery” (ECF 371) teachings undermine their claim to truth, particularly when cast beside the relative doctrinal unity of the catholic church. In addition to their chameleon-like views of scripture—at once accepting and rejecting it—Irenaeus notes the wide variety and inconsistency of Gnostic teachings and practice (ECF 362-67). His implicit argument seems to be that not all these claims can be true. The radical Gnostic diversity casts serious doubt on their claims to truth and apostolic authority, especially given the clear lineage between the contemporary church and the apostles, and the worldwide unity of church doctrine throughout that lineage (ECF 360).

Summing up, as described in the previous article, the Gnostic “gospel” as portrayed in The Hymn of the Pearl consists of three key elements: 1) the journey, 2) the slumber, and 3) the awakening. Through these elements The Hymn gives a Gnostic account of the disruption and restoration of the intended cosmic purpose. Within The Hymn’s Gnostic “gospel” there are motifs and imagery that are common to the biblical gospel, including a harmonious beginning, an episode of falling short, a divine plan of redemption, and a heavenly consummation. These common elements suggest how the Gnostic “gospel” could have appealed to the second century church.

However, arguments against Gnostic teachings, such as those articulated by Irenaeus in Against Heresies, ultimately preserved essential second-century church doctrine. Irenaeus’ arguments included a response to Gnostic attacks on the authority of apostolic teaching and scripture, their claim to a secret oral tradition, and a summary charge that Gnostic teachings are highly inconsistent.

Pingback: Irenaeus of Lyons and the Opulence of God. - The Catholic Astronomer